Several years ago I stumbled upon a book by Jim Benes, titled Chicago Christmas – One Hundred Years of Christmas Memories. It’s a fantastic book recounting the Christmas events and headlines in Chicago from 1900-1999. The book gives us a look into Christmas during World War II.

Several years ago I stumbled upon a book by Jim Benes, titled Chicago Christmas – One Hundred Years of Christmas Memories. It’s a fantastic book recounting the Christmas events and headlines in Chicago from 1900-1999. The book gives us a look into Christmas during World War II.

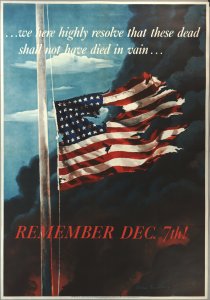

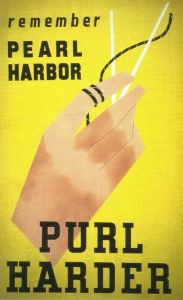

1941: Christmas fell 18 days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. People were still in shock of the attack and only beginning to realize what itmeant for the U.S. to be engaged in war with Japan and Germany. Off the west coast, Japanese submarines were shelling and torpedoing American freighters, within sight of the coast. People were in a panic to move inland and mass transit towards the safety of the Midwest was in high demand.

People were learning how to ‘black out’ their homes and businesses to prevent air raids. If lights on the ground could not be seen from the air, bombers may not see towns and cities as a target. Interestingly, a Police Captain from Chicago came up with the solution of how to safely keep traffic lights burning, but block them from the air. He suggested installing caps above the lights on the lights. The caps remain today, and I’ve often wondered why!

1942: Outdoor Christmas light displays were allowed, but they were subject to emergency blackout orders. The War Production Board asked that such lighting be eliminated entirely across the country.

It was a record cold Christmas. Heating oil was being rationed and fear of shortages was causing panic. Federal Price Administrator Leon Henderson allowed thirteen states to move up the start of the next rationing period by two weeks, easing some worry.

Newspapers all over the country ran columns and columns of the names of hometown heroes earning promotions or being injured. There was heavy fighting in Russia and American fliers were “expressing amazement at the amount of punishment their sturdy B-17s could take and keep flying”.

Benes shared the story of one family in Blue Island, IL. A mother of eight was in the hospital and in dire straits to the point she had told her children Santa had been killed in the war. The local Kiwanis Club decided to play Santa in order to change the message.

The top song of the season was White Christmas by Bing Crosby, newly recorded. Another favorite song was Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition and There’s a Star-Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere.

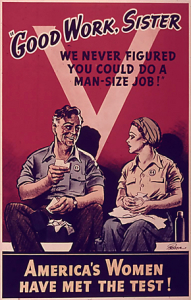

1943: Chicago’s temperature reached forty-six degrees on Christmas. It was a holiday off for many plant workers. It was a special day to not work…New Year’s Day a week later was a normal working day for the war effort.

On board Great Lakes Station in Chicago, sixty-six thousand sailors and WAVES were stationed and enjoyed a Christmas dinner: 10,000 mince pies, 35,000 pounds of sweet potatoes, and 61,000 pounds of turkey. Of course, this meant a shortage of such on the civilian tables.

If you could find a turkey to buy, it would cost 50¢ a pound (equivalent of $6.68 in 2015).

1944: A cold and snowy Christmas left slippery sidewalks and roadways. The Battle of the Bulge waged in Europe, Hitler’s last-ditch offensive. Sadly, news surfaced on Christmas Day that orchestra leader Major Glenn Miller had been missing since December 15th when his plane disappeared between England and Paris.

Turkey, still scarce, cost 49¢ a pound (equivalent of $6.72 in 2015), cranberry sauce was 20¢ for a sixteen-ounce can plus forty blue ration points (equivalent of $2.70 in 2015).

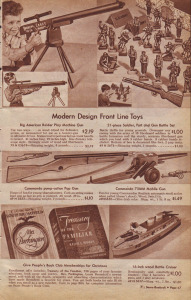

Under the tree little boys may have found metal trucks, electric football or baseball games. Little girls may have found baby dolls with their own suitcases, bottles, and changes of clothes. The dolls drank and wet (cost $1.98 then, $26.70 today’s equivalent).

1945: “This is the Christmas that a war-weary world has prayedfor through long and awful years,” declared President Harry Truman as he lit the national tree on Christmas Eve. “In love, which is the very essence of the message of the Price of Peace, the world would find a solution for all its ills. I do not believe there is one problem in this country – in the world – today which could not be settled if approached through the teaching of the Sermon on the Mount,” he told a nationwide radio audience.

Many homes were reunited for Christmas. …but only if they could get a train home! In Los Angeles 1,900 soldiers were being held aboard their ship because staging camps were filled. Another 75,000 soldiers were nearing the coast. Forty-five thousand men were awaiting trains in San Francisco, 27,000 in Los Angeles, 17,000 in Se attle, 4,500 in Portland. An additional 110,700 were expected to arrive on the West Coast within the following week. 94% of eastbound passengers from the west coast to Chicago were military personnel. Schedules went to the wind and special train routes were called in, but there was no way to accommodate all of the soldiers returning home. Police officers were called in to stop riots, Governor Dwight Green called up five hundred Illinois reservists and more than one hundred jeeps and trucks to help shuttle servicemen out of the area.

attle, 4,500 in Portland. An additional 110,700 were expected to arrive on the West Coast within the following week. 94% of eastbound passengers from the west coast to Chicago were military personnel. Schedules went to the wind and special train routes were called in, but there was no way to accommodate all of the soldiers returning home. Police officers were called in to stop riots, Governor Dwight Green called up five hundred Illinois reservists and more than one hundred jeeps and trucks to help shuttle servicemen out of the area.

Among the rail passengers who passed through Chicago in the days before Christmas was Col. Jimmy Stewart. He was on his way to Pennsylvania to spend the holiday with his mother. Stewart told reporters that after he received his air force discharge in February, he planned to start work on a new picture: It’s a Wonderful Life.

(Photos of the Sears Wish Book, years 1942-1943. Found on www.wishbookweb.net)

Find Jim Benes’ book here.