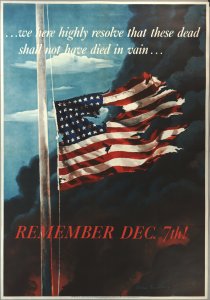

In the United States, February 3rd is Four Chaplains Day and commemorates the events of February 3, 1943, when the troop ship USAT Dorchester sank. Dorchester left New York on January 23, 1943, carrying 4 chaplains and about 900 other soldiers.? The story hit hard on the home front.

Even though being escorted by three Coast Guard ships, the Dorchester was torpedoed by a German submarine near Newfoundland at 12:55 a.m. on February 3rd, 1943. When the Dorchester began to sink, four chaplains of different religions, George L. Fox (Methodist), Alexander D. Goode (Jewish), Clark V. Poling (Baptist) and John P. Washington (Catholic) helped to calm the passengers and organize an orderly evacuation.

Life vests were passed out, but the supply ran out before everyone had one.

Survivors recounted that the four chaplains gave their own life vests to others, linked their arms together, called out prayers and sang hymns as they went down with the ship.

Usually, the story of unfathomable courage and sacrifice ends there.? But there is a very important next chapter to the story of The Four Chaplains.? It?s a chapter about the answer to their prayers.

Charles W. David, Jr. was a Coast Guard petty officer aboard the Comanche, one of the ships assigned to escort the Dorchester.? Because Petty Officer David was black and the military was heavily segregated, even though he had natural and acquired very useful skills, he was held to the lowest ranks.? When the Dorchester sunk, he was the fifth-lowest ranking member of the crew.

Self-sacrificially he became the answer to the chaplains? prayers. Without any obligation to do so, given his low rank and disrespect shown to him just for the color of his skin, he jumped into the freezing waters to save as many drowning men as he possibly could. Over and over, he dove back in the water to save more while other crewmembers stood woefully immobile on the deck, too fearful to go into that kind of danger.

674 souls from the Dorchester lost their lives. The Coast Guard ship Comanche rescued 93 of the 227 survivors, many of those from the efforts of Petty Officer David.

For his bravery and unyielding efforts to answer the call, Coast Guard Petty Officer Charles W. David, Jr. died a month later from pneumonia.

He was awarded the Navy & Marine Corps Medal for heroism in 2013 and a Coast Guard cutter bears his name.

When you hear the story of the Four Chaplains or when you tell people of the Four Chaplains, remember to continue the story all the way through to the answer to their prayers.

Read more: The Immortals by Steven Collis

![IMG_20150215_162036063[1]](https://www.thewarinmykitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/IMG_20150215_1620360631-300x168.jpg)