In the far corner of a grassy clearing within a national cemetery in Joliet, Illinois stands a life-size bronze statue of a WWII-era worker carrying a lunch box.

It is stationed on a pedestal with the names of 48 home front war workers, killed when the plant they were working in on June 5th, 1942 exploded at 2:45 am. Another 46 were injured. Not one person in the building escaped without serious injury.

In 1940 the small town of Elwood, Illinois became a major preemptive player in a war that its country was not yet participating in.

What was the site of 40,000 acres of farmland, home to 450 farms that dated back to the original pioneers of Illinois settlement, became property of the federal government through the process of eminent domain.

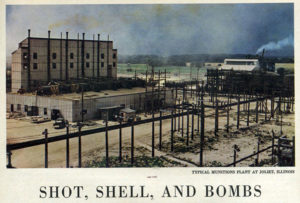

Two government contracted companies joined on the property to form what was commonly known as the Joliet Arsenal. One company manufactured various types of explosives for use at other plants and the other loaded artillery shells, bombs, mines and other munitions. One started production in July of 1941, the other in September of 1941 — months ahead of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

At its peak during WWII, over 10,425 war workers were employed at the two plants. One loaded more than 926 million bombs, shells, mines, detonators, fuses and boosters. The other produced over 1 billion pounds of TNT. The grounds of the operation held 1,391 buildings.

No one will ever know what exactly caused the explosion that was felt for a 100-mile radius and left a 12-foot deep crater where Building 10 once stood. At the time, anti-tank mines were being loaded into railroad boxcars, ready for shipping. They were pressure mines, designed to set off when weight rolled on top of them. The mines were packed five to a box, with an additional tetryl fuse booster for each mine. Used in blasting caps, tetryl sets off the rest of the mine. Two railroad boxcars were already filled with mines and fuses. A third was nearly full. Perhaps as many as 12,000 mines — 57,000 pounds of TNT. Source: Stephen Jesse Taylor

From a United Press newspaper article written at the time, “Explosion shattered buildings of one of the units of the $30,000,000 Elwood Ordnance plant gave up the bodies of 21 workers Friday. Army officials said 36 more were missing from the blast that could be felt for a radius of 100 miles. Another 41 were injured, five of them critically, from the explosion that leveled a building…. Not one of the 68 men inside the shipping unit when the blast occurred escaped death or injury.”

“The explosion put one of the 12 production units out of action temporarily, but operations continued in the others.”

And that’s how important war work was — worth giving up a life. Some remains of those lives, never found, were only identifiable by pieces of jewelry found at the site. But the work had to go on. It was too important to stop. This was essential work and essential workers were doing it.

At least two widows, whose husbands had died in the blast, later went to work at the arsenal. Charlotte Hammond started working July 5, only a month after her husband’s death. She had bills to pay and few other choices, so worked in the mail room. Isabel McCawley, widow of Lawrence A. McCawley, went to work at the plant packing TNT.

According to a 75th anniversary article in the Chicago Tribune, Bernie Levati was not alive when his uncle Frank Levati, the oldest of the four brothers in his father’s family, was killed. The other three boys served overseas during the war and all returned unharmed, she said. Only Frank, who remained at home, died.

“The loss goes farther than that. I never got to meet my grandfather, who died a year and a half later of a broken heart,” Levati said.

The Joliet Arsenal finally stopped production in 1976 and closed for good in the 1990s. The property where it once stood is partially in ruins and very much so in recovery. The land has been turned over to the U.S. Forest Service to be restored as the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie. Another 1,000 acres was given to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs for the national cemetery.

Other Interesting Articles:

From the Chicago Tribune: Click Here

From the Daily Journal: Click Here

From the University of Illinois: Click Here