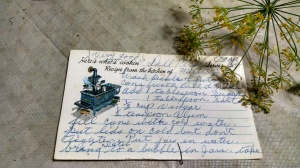

Twice in a year, Mrs. Ben Prochnow of Markesan, Wisconsin was allowed two large quantity ration certificates for sugar for canning purposes. On June 13, 1942 Mrs. Prochnow received 39 pounds of sugar and on August 14, 1942 Mrs. Prochnow received 54 pounds of sugar.

As the policy went, the summer ration was set to each person being allotted one pound of sugar per 4 ½ quarts of fruit, plus an additional one pound for canning of preserves. The fall ration however, mention anxiety on the part of the government (OPA office) that “government is as anxious to have all available fruit canned as it is to conserve sugar. For that reason local boards have been instructed to issue sugar purchase certificates at the second canning sugar registration based entirely upon legitimate requirements of sugar.” The base calculation would still be one pound of sugar for four quarts of canned fruit. Housewives — in this case, Farmwife, would need to come to the registration point with a worksheet in hand showing her calculations to receive her fair share.

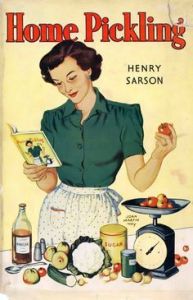

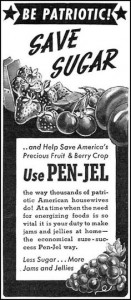

On the honor system, women calculated their kitchen work and even though there seemed to be rule of plenty, they still took to other suggestions of stretching canning and preserving rations.

Sure-Jell advertised more than twice as many glasses of jelly, jam or marmalade with their product. Touted as “Sensible” and “Patriotic”, who wouldn’t be caught not using it?

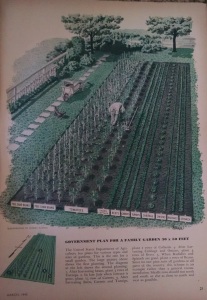

According to the 1943 Canning for Victory pamphlet, compiled by the Rector’s Guild of the Grace Episcopal Church in Madison Wisconsin, canning seasons in North Central States looked something like this:

June: Pineapple, Rhubarb, Strawberries

July: Cherries, Currants, Gooseberries, Huckleberries, Raspberries

August: Blackberries, Peaches, Plums

September: Apples, Crab-apples, Grapes, Peaches, Pears, Quinces

Vegetables:

June: Asparagus, Beans, Carrots, Greens, Peas

July: Beans (string), Carrots, Corn, Greens

August: Beans (string), Beans (lima), Beets, Corn, Tomatoes

September: Pumpkin, Tomatoes

Fowl:

September: Chicken, Guinea-hen

October: Duck, Grouse, Pheasant, Partridge

November: Duck, Grouse, Partridge, Rabbit, Turkey

December: Duck, Grouse, Partridge, Turkey

The pamphlet states that as little as ¼ cup sweeting to 1 ½ cups of water may be used if desired. Fruits may be canned with or without sugar, but the color, flavor and shape of the fruits are better if a little sugar is added. When canned without sugar, no water need be added to juicy fruits as berries, cherries, currants or plums.

Backtracking…the difference between jelly, jam, preserves and marmalade? In a nutshell here it is:

In jelly, the fruit comes in the form of fruit juice. In jam, the fruit comes in the form of fruit pulp or crushed fruit and is less stiff than jelly as a result. In preserves, the fruit comes in the form of chunks in a syrup or a jam. And finally, in marmalade a fruit preserve is made from the juice and peel of citrus fruits boiled with sugar and water.

If we were to imagine what Mrs. Prochnow’s fruit cellar looked like at the end of canning season, with her total 93 pounds of sugar and saying she did not incorporate the advice for stretching her allotment, we would likely see 25 quarts of canned fruits and preserves all lined up on shelves in pretty summer and autumnal tones. More likely, she did use the advice and made smaller batches of pints. Perhaps an entire wall would be lined with 50 various types of fruits. Add it to the vegetables and non-sweet produce and you would see a full room of Mrs. Prochnow’s work. What a sight it must have been.