VE-Day. Memorial Day. D-Day. The anniversaries of these dates mark a time when people all over the world pause to reflect. Veterans’ stories and vivid images are replayed to help us recall the memories and honor those who made the ultimate sacrifice.

I welcome the extra attention given to WWII history at this time of the year. And I aim to add to it.

In my time dedicated to remembrance, I also observe June 5th, 1942, the date an explosion at the Joliet Arsenal in Ellwood, IL killed 48 war workers and injured another 46. (See a previous post about this accident.)

Elwood is local to me, and other ordinance plant sites are not too great of a distance either. I recently visited the Badger Ordnance Works site and museum (B.O.W.) near Baraboo, WI. The museum is maintained by the Badger History Group and well worth the trip to view their collection of artifacts and meet the curator, Verlyn Mueller, who is happy (and well equipped) to answer all questions.

The B.O.W. plant began construction in early 1942 and operated through the Vietnam War. Production lines included smokeless powder, acid, sulfuric acid, rocket propellant, and Ball Powder. On 10,565 acres the plant produced 1,035,542,500 pounds of propellant used in ammunition through three wars. (Source: Badger History Group, Inc.)

Near the entrance of the museum is a special memorial and a beautifully landscaped reflection area. “The Land Remembers the Footprints of the Past: a tribute to the families who gave up their land and homes for the defense of their country in World War II to the Badger Ordnance Works”. The war work being done inside the buildings on the property of these arsenals called for the ultimate sacrifice of the land as well. Throughout the United States, much of the property taken and used for these ordinance plants can never be safely returned to its original farmland use.

One of the displays inside at the B.O.W. Museum includes a newspaper clipping reporting about four men killed in an explosion on July 19, 1945 – just weeks before the end of the war. Erwin Pugh, William Denny, Elsworth Goff, and Mark Shearer are buried together in a cemetery just east of where the plant was located. On a rainy Saturday afternoon, my husband and mother, who are always up for one of my WWII history tracking adventures, helped me locate the gravesite of the war workers.

The museums I visit and the stories they tell always have an interesting way of connecting people, places, or things one to another.

The powder that B.O.W. produced was sent to other plants in nearby states for the next phase of ammunition production. Some materials went to The Twin Cities Ordnance Plant in Minnesota, and some went to the Green River Ordinance Plant near Dixon, Illinois.

Before my visit to B.O.W. I was aware of a fatal explosion at Green River Ordinance Plant (GROP) that involved a woman but did not have many details. Again, the curator of the B.O.W. museum said something he had heard or read about GROP that inspired me to learn more on my own. According to an interview with Molly Gosney, one of the women who worked the line that produced rifle grenades, “…workers were warned that if they discovered a grenade with the clip missing, they were to hold the grenade close to the body and call a supervisor who would take care of it.” (Source: Memories of the Green River Ordnance Plant 1942-1945, Dixon Public Library).

On February 29, 1944, that is exactly what war worker Edna Christy did. Research has brought me to two possible explanations of what may have caused a grenade explosion, but the ending is the same. Edna Christy, a widow at age 38 died at the local hospital. Eleven others were injured, but not seriously. In fact, according to a Bureau County Tribune newspaper article dated March 3, 1944, four of the injured women returned to their posts in the afternoon “more determined than ever to put the finishing touches on hitting power that will hasten the day of Victory on the Allied battlefronts”. Witness reports say that quick-thinking and catastrophe training went into effect, one war worker sounding an alarm to evacuate the building quickly and using fire extinguishers on resulting blazes. A loose pin was found near the area where Edna had been working, indicating that she was handling a live grenade. Holding it close to her body ended her life but saved many lives around her.

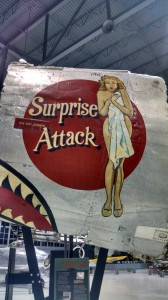

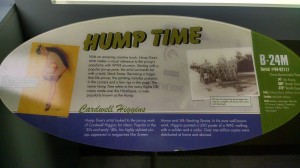

As I researched further, I learned that Edna Christy was buried two days later in Princeton, IL next to her husband who had died only four years earlier at the young age of 32 when he received a fatal shock from an electrical welding machine which had short-circuited. Perhaps this was another fatal workplace accident? The Bureau County Tribune reported later that Edna’s son attended her funeral. His name was Bruce and he was 20-years old, serving as a tail and waist gunner aboard Fighting Fortresses in the Pacific. He visited the ordnance plant while in the area for his mother’s funeral.

Thanks to gravefinder.com, I was able to view the gravesites for Edna and Bruce, and happy to know that Bruce made it through the war, but saddened to realize that he died young as well at the age of 33-34 in 1957. He’s not buried next to his mother, but in a cemetery four hours away with a simple headstone that gives no indication of his military service.

I can’t help but wonder about Edna and her time working at GROP. From so many other stories I’ve read or heard, I can imagine her on a bus making the 30-mile route from where she lived in Princeton, IL to the plant in Dixon, IL six days a week, alternating shifts each week working 7:00am-3:00pm or 3:00pm-11:00pm or the much dreaded 11:00pm-7:00am shift. I wonder if she made friends while working there. So many of the other war worker testimonials describe feelings of pride in their work, especially knowing that the shells they were making were going into the hands of their sons — something that Edna had to know with her son credited for missions at Guadalcanal, Midway, and Wake Island.

For every war worker in all of the ordinance plants – 77 newly built and all 8,000 total plants that had contracts by the end of the war, we owe a huge debt of gratitude. The war workers’ contribution to our freedom was not in the form of bravery on the shores of Normandy, but as incredible courage displayed on the home front knowing that accidents inside the plants were common and could very well be fatal. They knew this and even yet, millions of them went to work every day to do their part, dedicated to the ideals of democracy and what Americans could achieve when working together.

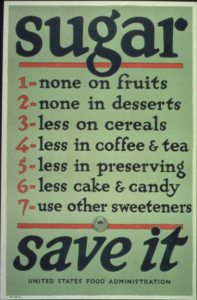

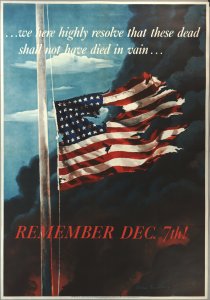

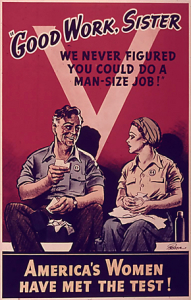

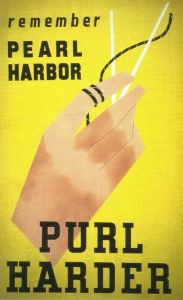

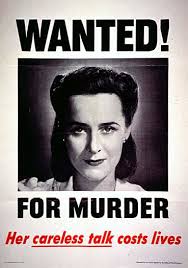

“propaganda” is thrown around a lot when it comes to the government ads asking for commitment and loyalty to the war effort. To the fact that the government was even taking out ads to sell war bonds and inform through pictures the need to not gossip, not participate in the black market for food – it seems a little bizarre today.

“propaganda” is thrown around a lot when it comes to the government ads asking for commitment and loyalty to the war effort. To the fact that the government was even taking out ads to sell war bonds and inform through pictures the need to not gossip, not participate in the black market for food – it seems a little bizarre today.